“Let's face it. We're undone by each other. And if we're not, we're missing something.”

Judith Butler

At around 18, I found myself, somewhat by surprise, in a small Franciscan monastery where I would spend the better part of my youth. A young monk in a dark blue habit with a brown belt had invited me after a university lecture in Leuven. I didn’t believe a word he said, so, in my innocent enthusiasm, I ventured to his monastery, mostly to question why he—and his brothers—gave up their lives for something so “unlikely.”

In no time, I had forgotten this quest. The bucolic, natural, and simple life required deeds, not words: my hands in the bread dough, digging mud in the garden, harvesting grain in the fields. All this intertwined with prayers, and more prayers, beautiful songs, sweet incense in the chapel, the orthodox icons on every wall, the comics of saints in the chapel closet that I read in my cell before going to sleep. Ultimately, I never really left, but spend five years living as a monk-at-a-distance.

During this time, I grew quite attached to the friendships I made with the brother-monks. We would go on pilgrimages, work long hours in the cow stables, prepare music for ceremonies, and rehearse for plays. But there was something peculiar about these friendships.

Most clearly, there were physical limitations: they couldn’t leave the monastery without permission. This meant that none of my brother-friends were present during important events like graduations, birthdays, or even when I left to study in the USA for five years, they were absent for my farewell party.

But that wasn’t what touched me most. After a while, it dawned on me that there was no reciprocity in the emotional vulnerability and investment either. The brothers were mostly present with kindness and openness, but I would rarely witness their lives: that would be preserved for their spiritual accompaniments with the abbot. After a painful disappointment -a brother suddenly disappeared after we had spend many days of traveling together- I started to rethink all my interactions and perceive them as quite shallow. The smiles and questions were still warmhearted and interested, but I now felt them as less sincere. I started wondering if it actually mattered who I was as a person.

Though painful, it was also clarifying: I came to the monastery to deepen my connection with God. The loneliness I felt after my brother-friend disconnected became a rich opening for worship. His disappearance into devotion to his Beloved -just like when a spouse returns home to his family and takes time to reconnect- led me to fall in love with Her as well.

Eventually, I left the monastery. I wandered for a while, trying to forget this calling, but rather unsuccessfully. Years passed, and after some twists and turns, and other experiments with monastic life, House of the Beloved was born.

Throughout it’s inception, we reimagined the monastic life, deciding to include connection and relationship—friendship, romance, and sexuality—as part of the path, along with all human experiences, including anger, rage, shame, lust, and more. We wanted these connections to be real and sincere, not hidden behind irrelevant conversations. Instead, we sought radical honesty, to touch and be touched, to be broken open, to pray and transform together. Our goal was to craft connection as a place of revolution, liberation, and deep self-recognition. Equally important: the other person is always the end, never a means for one’s spiritual gain or the greater glory of God.

So, how do we protect relationships from becoming instrumental, from using the other for our own spiritual or existential gain?

Inspired by Alain Badiou and Scott Peck, we adopted the definition of love as "the will to extend oneself to support the existential development of oneself and the other."

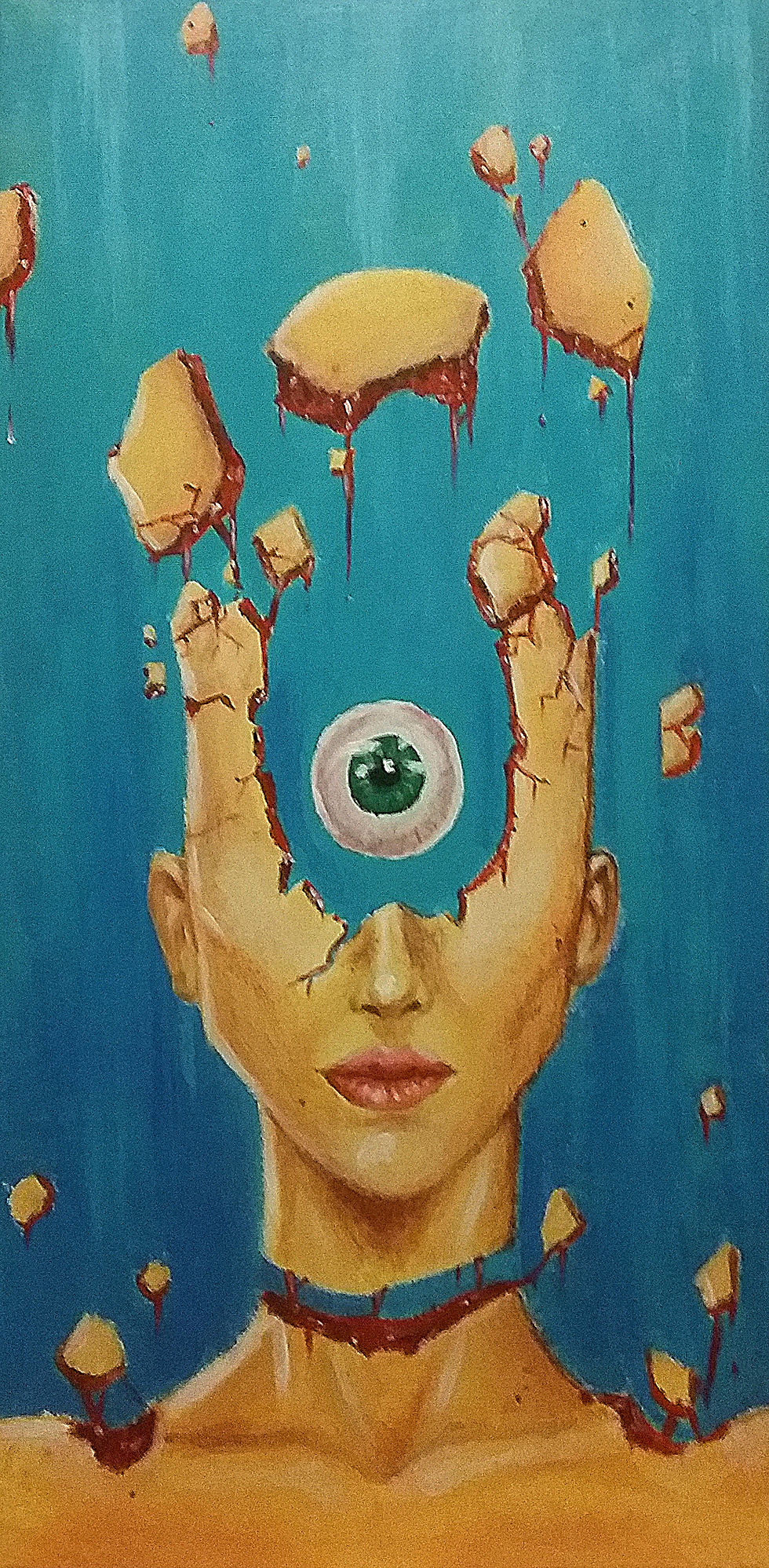

The key lies in the act of extending oneself. To truly allow the other to express their own way of being human is to offer "a petition to become undone" (Judith Butler). This means falling apart, allowing myself to be deconstructed, letting go of limiting identities, and making myself fully present and available to be devoured by the moment (Eric Baret). To be touched, triggered, and shaken. If I can witness this process and ask myself, "What makes it difficult for me to be with what is, without trying to make anything happen or prevent anything from happening?" then it has the potential to deepen my self-awareness and self-recognition. In this moment, means and ends coincide, and the process supports both our spiritual developments simultaneously.

This way of loving is at the heart of House of the Beloved. To be a monk doesn’t mean taking refuge from the world—quite the opposite. It means diving in more fully and putting everything at stake. It is not about distancing oneself from others but drawing closer, offering the other a petition to become undone. This path is transformative, making us more human, more vulnerable, and more available to be deeply touched and connected.

Any monk who hides behind their calling to avoid being available and compassionate toward others is acting in misunderstanding.

So, what distinguishes monastic friendship from regular friendship? A monastic friendship, I suggest, is a mode of dispossession—a petition to become undone. In contrast, ordinary friendships are often a mode of possession: a way to fulfill our need to love or be loved, to be seen and heard, to reciprocally consolidate our identities, and a mutual emotional dependency that protects us from loneliness and the absence of care.

To conclude, the revolutionary and liberating power of monastic friendship lies in its radical willingness to become undone. It’s not about the comfort of mutual dependence or emotional security but about daring to be exposed and deconstructed in the presence of another. This vulnerability is what ultimately fosters existential growth, both for oneself and for the other, turning connection into a practice of liberation.

“Only to the extent that a wo.man exposes her.imself over and over again to annihilation, can that which is indestructible arise within her.im.” (Karlfried durkheim, gender-inclusive pronouns added)

*To become undone can be quite scary. Some unconscious conditionings can prevent us from staying really present with the other. If you want to make these unconscious patterns conscious, you can join a shadow work weekend. We look forward to supporting you on this path.

*You may also be interested in our podcast about love: "A case against love".

Comments